Rote vs Surface Level Learning

You peek into a classroom and see students in groups of three dynamically engaged. Not having fun engaged, but true intellectual engagement. Students animatedly defend their positions and exclaim when they discover a yet to be discussed idea. They are on a mission to uncover the critical attributes of the concept they’re studying. The teacher is circulating around and as students defend their ideas, she asks questions to poke holes in their reasoning or strengthen their argument. When teams of students demonstrate their initial understanding of the concept, the teacher now provides an additional resource that doesn’t completely align with their initial thinking. They have to refine their understanding and assimilate this new information into their schema they have constructed. Finally, learners look at a third context which continues to push their thinking and understanding of this individual concept. Students are ready to start connecting separate concepts and move to deeper levels of thinking because they have a strong conceptual understanding first.

The prior scene highlights the excitement and wonder that can come when learners are allowed to discover ideas before being explicitly told. Unfortunately, this is not always the case and many students go to class and repeat the same daily routine — warm-up, take notes, practice, start homework — without ever being given the chance to see the underlying structure or purpose of their content. We fall into a rut of rote learning (for various reasons that I completely understand). The test, needing high scores, pacing guides, and the way it’s always been done cause teachers to feel like they have to get through content and don’t have the breathing room needed for students to discover or explore. What I want to emphatically emphasize is that you don’t have to choose. Students can learn their content and discover if we design learning experiences that allow students to create understanding of concepts and not only rote practice.

What exactly is rote learning?

What do you think when you hear “rote learning”? If you’re like me memorization, basic skills, and boredom come to mind. Now take a minute and define surface-level learning. Did you think, ‘isn’t this a synonym for rote’? If you did, you’re not alone. Up until a year or so ago I also thought the two terms were synonymous with superficial learning that is neither meaningful nor engaging.

Rote learning is repeating information over and over until you’re able to recall it from memory. This type of learning results in the short-term ability to recall information but doesn’t lead to lasting learning. According to Finley’s article, “Why Rote Learning Doesn’t Work—And What Does Work?” (citing from Willis, 2007), states “rote memorization doesn’t work for students because there is no engaging pattern or effort made to relate the content to students’ lives.” It’s hard for students to see the purpose of what they’re doing when it is skill and drill and has no apparent connection to their current or future lives.

Cramming for a test, memorization of facts without understanding, skills practice without a corresponding concept are all examples of rote learning. Students have all of these isolated bits of information in their heads, but how often as a teacher have you had students “understand” information for a quiz or test only to have forgotten it the next unit? Or have had students swear the teacher the year before didn’t teach that topic? This is because rote learning requires only a simple amount of storage space in the brain and doesn’t require students to truly make sense of those facts they have memorized.

What’s the difference between rote and surface-level learning?

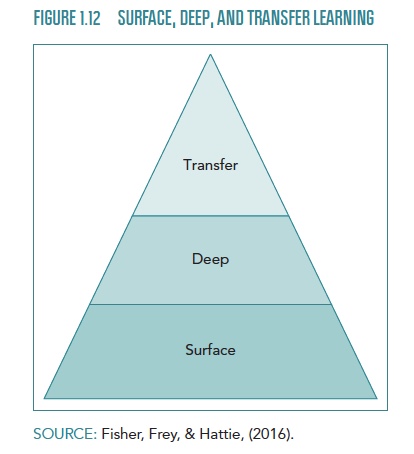

About this time last year is where the light bulb finally went off about the difference between rote and surface-level learning. (Cue the Hallelujah chorus.) Julie Stern was visiting two schools I support and included the graphic below in her presentation. She asked us to write down what we thought surface-level learning was, and as mentioned previously, I described it as rote or superficial learning.

While participating throughout the day, I realized just how wrong I was. Rote learning is the memorization of isolated facts. Surface level learning does require memorization, but it doesn’t stop there. “Surface learning does not mean superficial learning. Rather, surface learning is a time when students are initially exposed to concepts, skills, and strategies.” (Hattie, Fisher, and Frey, Visible Learning for Mathematics, 2017) In other terms, surface-level learning becomes meaningful because students will see how pieces of a concept fit together instead of these pieces staying fragments of information in their brains. Surface level learning leads to students retaining information from unit to unit, instead of merely recalling it for a test.

How do we build surface-level learning?

Two of my favorite strategies to help students develop a foundation level of understanding for key concepts in their classrooms are sorting and SEE-IT. Both of these strategies can be completed with paper/pencil or electronically, and the simplicity of implementing the strategy only increases your excitement when you see your students thinking deeply about concepts.

Sorting

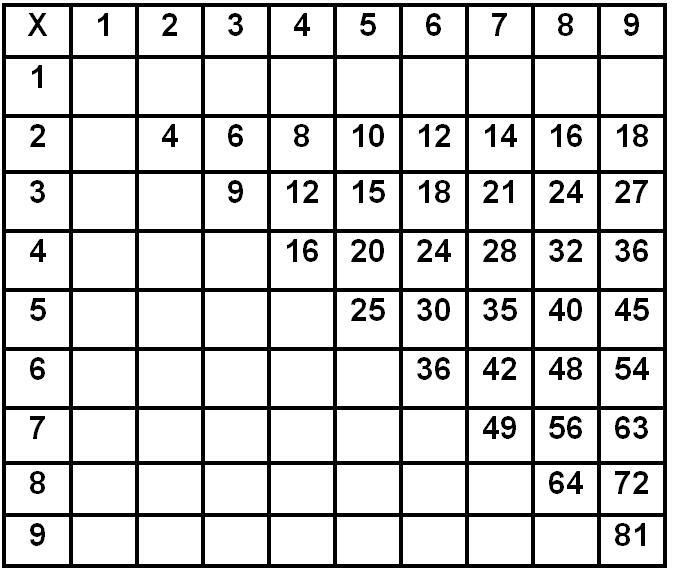

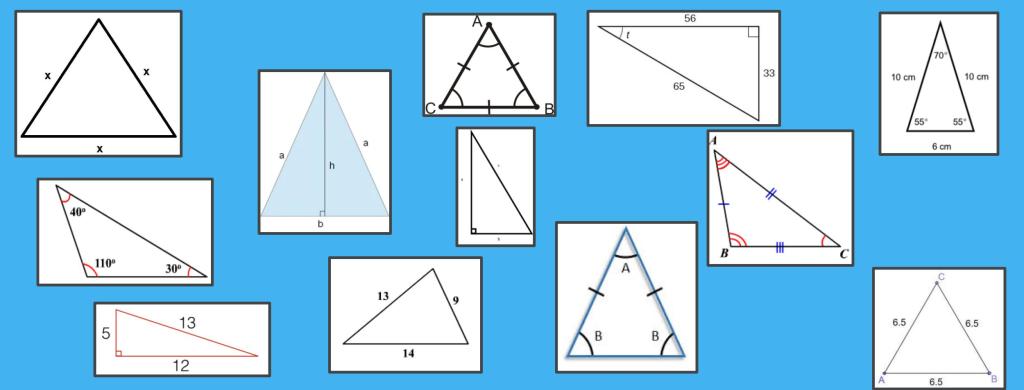

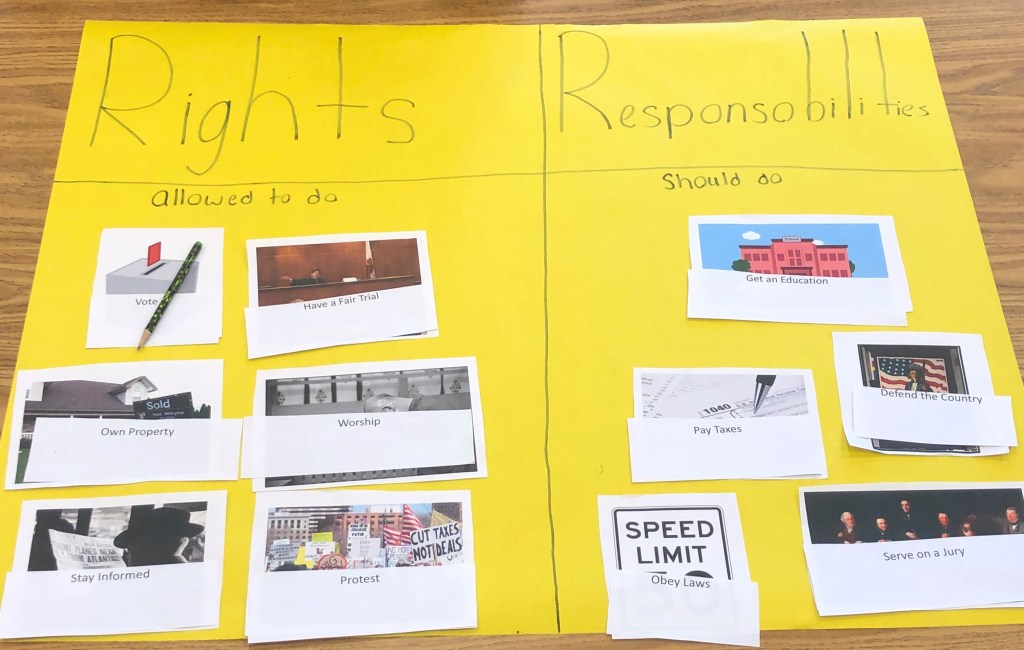

These are the traditional concept attainment lesson. This is a great strategy to help learners build a working understanding of concepts before being explicitly told a definition. When I have helped teachers implement this in their classrooms, or when I do it with professional learning, we start with a stack of cards containing examples of the concepts we are trying to highlight. We then ask the students to divide the cards into categories. (You can leave this open-ended and see what students notice first or provide a set number of categories as a scaffold.)

After students have conducted their original sort, you can circulate around and see what patterns they have picked up on, if they’re developing an understanding of the concepts, or if there are attributes they’re not noticing. You can then provide a second piece of information to help students refine their thinking which would possibly cause them to have to re-sort their categories. (Make sure as you observe students working you ask them how they determined their categories. Ask what-if questions to poke holes in their thinking or to force them to justify and defend their ideas.)

Once students appear to have the general idea of the concept, you can then begin introducing a variety of new images that are examples and non-examples. Students use their criteria from their sorting to distinguish between the two, and the teacher again questions and probes students to provide a rationale for their responses. By this point in the lesson, students have had a chance to make meaning of the concepts and it’s time for the teacher to introduce the formal definition. Now when they writing the definition in their notes, they understand what they’re writing.

Examples: On the left, 6th grade mathematicians extend their learning of identifying triangles based on the size of angles to identifying triangles based on their sides. This leads into a conversation about how to find rule for area of a triangle that works every time.

On the right, Elementary historians make sense of rights and responsibilities in their social studies unit. This leads to a debate about what is a right or responsibility, how to distinguish between the two, and the topic of are there universal rights.

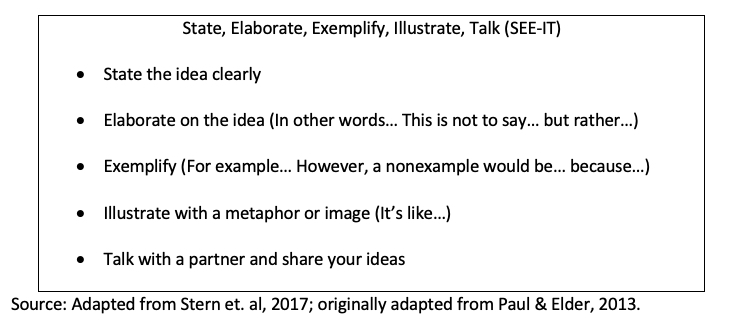

SEE-IT

This is a very simple strategy that starts with the teacher providing a complex explanation or definition for the target concept. Students then make sense of this concept and restate it in their own words. They should use their resources to help answer any questions they have and deepen their understanding. Learners then create their own examples and illustration. After they have had a chance to complete this step, they should talk with peers and compare their responses. A tip from Julie Stern is to pay close attention to the illustration and examples as this is where you will be able to see how well a student understands or misunderstands the concept.

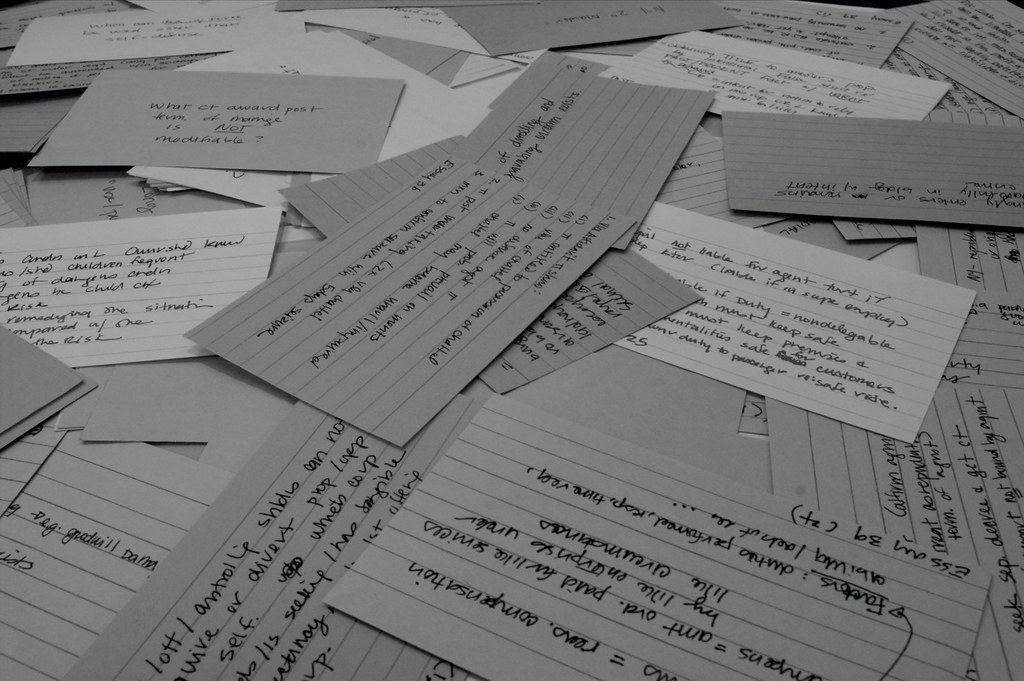

Recently, teachers I work with have had students do the SEE-IT strategy on index cards. They then add these cards to a silver key ring so that all of their concepts are saved in one place. Throughout the unit, the teacher will ask students to get their concept cards and will ask them to discuss the relationship between various concepts. (This is once students are at a deep level of understanding which will be highlighted in a future post.) An additional variation for younger students it to call it SEED – State, Explain in Own Words, Example, Draw it. We tell these primary students we are planting a SEED garden and as we learn more about concepts our thinking will bloom just like a flower garden.

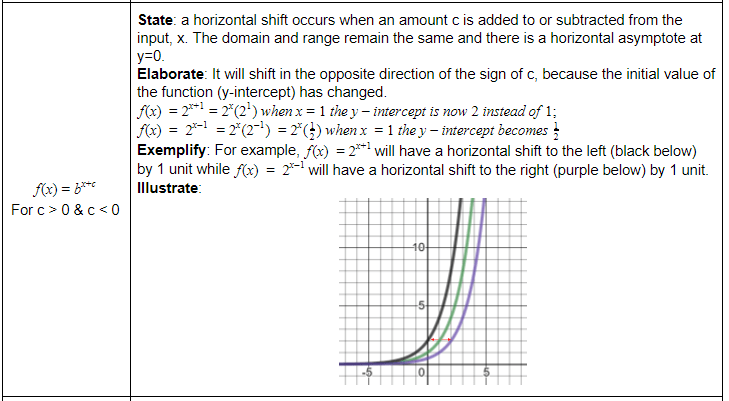

Examples: Top – Algebra 2 mathematicians explore transformations of exponential functions and then create SEE-IT cards to solidify and demonstrate their understanding.

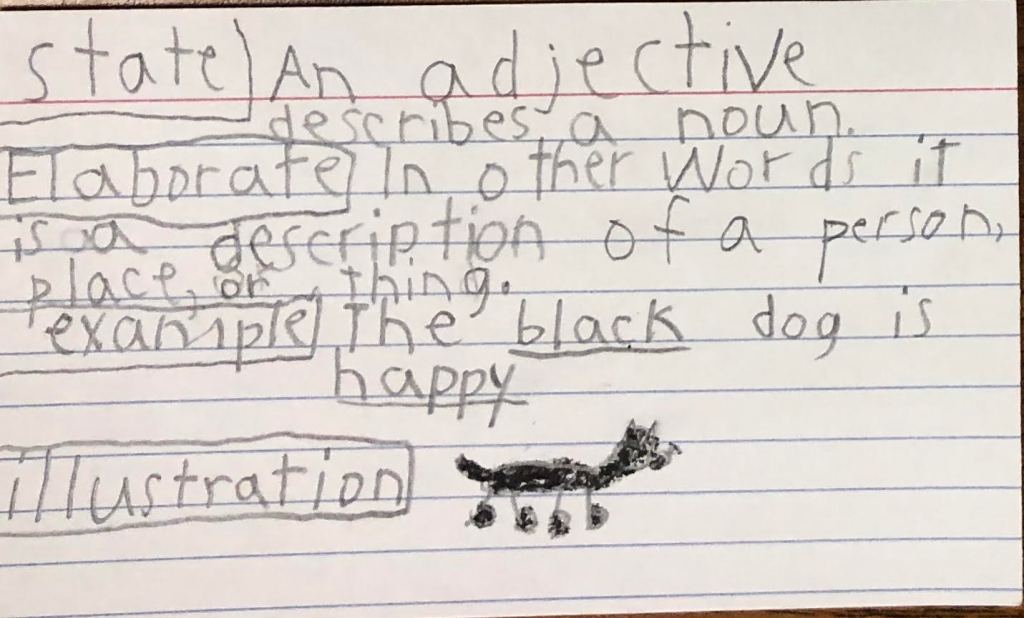

Bottom – Future authors in a 2nd-grade class generated SEE-IT cards for parts of speech.

What I love about both of these strategies is that they require students to create their meaning of a concept by putting it in their own words and promote academic discourse which will allow them to learn from and with their peers. For more strategies for building a surface-level understanding of concepts look at Julie Stern’s Tools for Teaching Conceptual Understanding books available for elementary and secondary teachers.

Final Thoughts

To be clear — I’m not saying memorization = bad. This is far from the truth. Students need do need automaticity and the ability to recall certain information quickly. What I am advocating, now that I understand the difference, is that we anchor activities with corresponding concepts so that students have a way to make sense of the facts, skills, and processes they are learning. Instead of disparate bits, let’s help students organize the information in their heads and maybe next unit they will have retained a little more than has been seen in the past.

A special thank you to Trevor Aleo, Melanie Smith, Gina Thompson, and Jesi Hilliard for your wordsmith sessions, brainstorming, collaboration, and friendship.